The Detroit Repertory Theatre’s new production, Roaming Charges, reminds me of a college professor I had at Wayne State University. Dr. Julie Mix had given a writing assignment, I turned it in, accused of plagiarism. “It’s rare that a first year writing student would write an essay of this quality,” she reasoned. To fix her curiosity she asked me to meet her in her office where I was instructed to write another essay. I had mixed feelings about this. On one hand, I felt it quite complimentary that my professor liked the essay. On the other hand, I wondered if she’d have questioned my work if I were white. Whatever the case, I appreciated her honesty. Ralph Accardo’s play reminded me of that tensed moment of my freshman year, but unlike Dr. Mix, the problem with Accardo’s play is that it is not honest, just more coded language to affirm a particular hidden agenda: black folk are inferior and white folk are superior. That’s the underline message of Accardo’s play, Roaming Charges.

The Detroit Repertory Theatre’s new production, Roaming Charges, reminds me of a college professor I had at Wayne State University. Dr. Julie Mix had given a writing assignment, I turned it in, accused of plagiarism. “It’s rare that a first year writing student would write an essay of this quality,” she reasoned. To fix her curiosity she asked me to meet her in her office where I was instructed to write another essay. I had mixed feelings about this. On one hand, I felt it quite complimentary that my professor liked the essay. On the other hand, I wondered if she’d have questioned my work if I were white. Whatever the case, I appreciated her honesty. Ralph Accardo’s play reminded me of that tensed moment of my freshman year, but unlike Dr. Mix, the problem with Accardo’s play is that it is not honest, just more coded language to affirm a particular hidden agenda: black folk are inferior and white folk are superior. That’s the underline message of Accardo’s play, Roaming Charges.

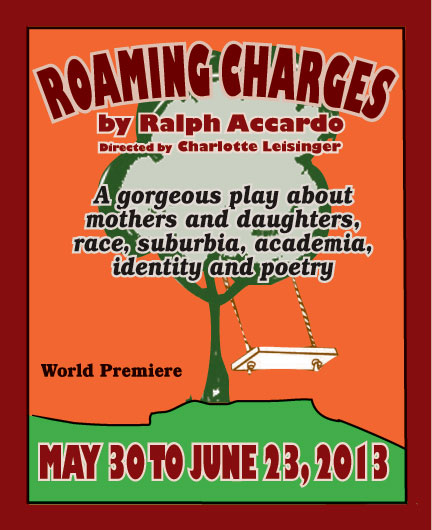

Lacey Cuppard (Kristin Dawn-Dumas) is a precocious thirteen year-old, swinging in the park, writing her wonderful poems. Everything was going well until Kate (Leah Smith) come along and reminds Lacey that black folk don’t write brilliant poems. Like Olaudah Equiano snatched from his African village, Lacey’s innocent is shattered and her disappointment surfaces. To make matters worse, Kate indirectly accuses Lacey of plagiarism. At this point, Lacey’s innocence is totally busted. She throws a barrage of sensitive questions at Kate, accusing her of feeling sorry for the little black girl; only taking interest in the little black girl’s poems because she must think Lacey’s parents too dumb to recognize their daughter’s gift. Lacey accuses Kate of playing games with her, playing on her intelligence, to think that she is too stupid to recognize, comprehend and understand racist condescension.

But Accardo is playing games, too. He’s Lacey’s real problem, to think that he could articulate the issues and problems of a thirteen year old black girl, from a serious and critically observant position. Accardo had no intentions of helping Lacey or Solving Kate’s entrenched racism. Kate admits it: most white people will never admit how they truly feel about black people. Lacey cannot help Kate find redemption for her prejudiced feelings towards black people, but that is not the agenda here. Accardo’s play seems more like an Aristotelian mimesis, perhaps, where the playwright’s purpose is to examine his own racial fears and prejudiced hang-ups. Roaming Charges is only here to re-affirm the social order. Accardo ducks down low, behind the garbage can (or in it) like a thief returning to the scene of a crime.

Black folk cannot trust white writers with our humanity. We cannot trust white writers with the more delicate issues concerning black love and compassion and forgiveness and redemption and hope and fraternity. We always lose. Roaming Charges only achieves Accardo’s point to carry on the tradition of American literature (which really means white literature) by perpetuating white supremacy. Rather than a fair, square representation of African-American women, for instance, all we get is Accardo’s fears and prejudices put on full public display. Perhaps Lacey’s character should be named “Pozzo” (a Beckett symbol for new forms of disrespect and degradation, as Cornel West once noted). Accardo clearly has no clue about black humanity or black women. If he were serious about exploring themes of race, suburbia, academia and identity, he shouldn’t even be casting black folk.