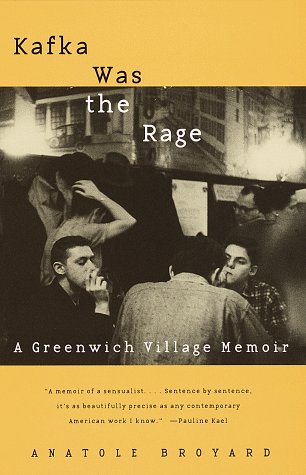

I arrived in Michigan later than I’d originally planned. I made an appointment with Sylvia Hubbard to discuss matters of writing, books, literary criticism, my practicum and, once again, the current state of urban literature. I was also eager to talk to Sylvia about her collection of short stories, the purpose of literature, and my new disappointment with Anatole Broyard’s posthumously published memoir, When Kafka Was the Rage: A Geenwich Village Memoir.

I arrived in Michigan later than I’d originally planned. I made an appointment with Sylvia Hubbard to discuss matters of writing, books, literary criticism, my practicum and, once again, the current state of urban literature. I was also eager to talk to Sylvia about her collection of short stories, the purpose of literature, and my new disappointment with Anatole Broyard’s posthumously published memoir, When Kafka Was the Rage: A Geenwich Village Memoir.

I drove up Linwood, north of Downtown Detroit, west of Woodward searching for a convenience store that sold Pall Mall cigarettes in the green box. I drove past Richton Street where as a child I spent bright festive summers with anxious cousins riding red bicycles in clean streets, eating ice cream cones on sunny days while frolicking along neat colorful streets in safe neighborhoods. I past Cortland Street in search of the two story house on the left. I arrived early. I sat in my car, lit a cigarette and reflected on Broyard’s memoir.

The book opens in post WW II Greenwich Village, with Anatole fresh out of military service returning to Brooklyn to reunite with his parents. Broyard’s observations of Greenwich Village are good, and his critiques are thorough. We see GV through Broyard’s eyes with candid and surreal snapshots of bourgeoisie life and privileged spaces. Broyard’s writing is crisp and his style is intellectual. He discusses matters of the heart and whatever he considers worthy of mention. He liked being a student at the New School, he liked fucking, loved art, dancing, underworld activities, and his relationship with Jews is ambivalent at best. Literary criticism was enjoying a vogue and the love of books also became a significantly new social status among the GV crowd. Broyard explains:

It was as if we didn’t know where we ended and books began. Books were our weather, our environment, our clothing. We didn’t simply read books; we became them. We took them into ourselves and made them into our histories. While it would be easy to say that we escaped into books, it might be truer to say that books escaped into us. Books were to us what drugs were to young men in the sixties. (29-30)

Broyard grapples with the fact that his good friend Saul is dying of leukemia and what it means to confront death. Anatole writes, “You need leisure to think about tragedy. Maybe you can face it only in the absence of the person, after the fact. Or you can do it only when you yourself are in despair” (103). I thought back to my conversation with Sylvia and about death in the context of the current issues pervading African American literature and art, and I thought about Wallace Thurman’s disappointment with the Harlem Renaissance and its “failure to organize Harlem Renaissance writers into a cohesive literary movement,” and how it informs and situates my own disenchantment with the current state of black literature. I also began to understand more deeply Broyard’s decision to pass for white in order to not be racially pigeonholed in the literary world as a whole. To be or not to be, that is the question.

Perhaps my disappointment with Broyard’s memoir had more to do with a personal issue than an aesthetic one. (The confirmation of what I had thought and believed?) Broyard completely disassociates race from his reflective discussion and memory of his life in Greenwich Village and his life before that. He only provides faint allusions to his family, but never takes us into any real deep moments which would shed light on his transformation into the man he ultimately became. Suddenly, near the end of the book, I realized that Broyard was passing. With further research on the matter of Broyard’s peculiar omission of racial heritage I came across an interesting piece by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. titled “The Passing Of… “I thought back to the conversation between Sylvia and I, and what it meant to be a black writer today.